|

Maggie in London:

|

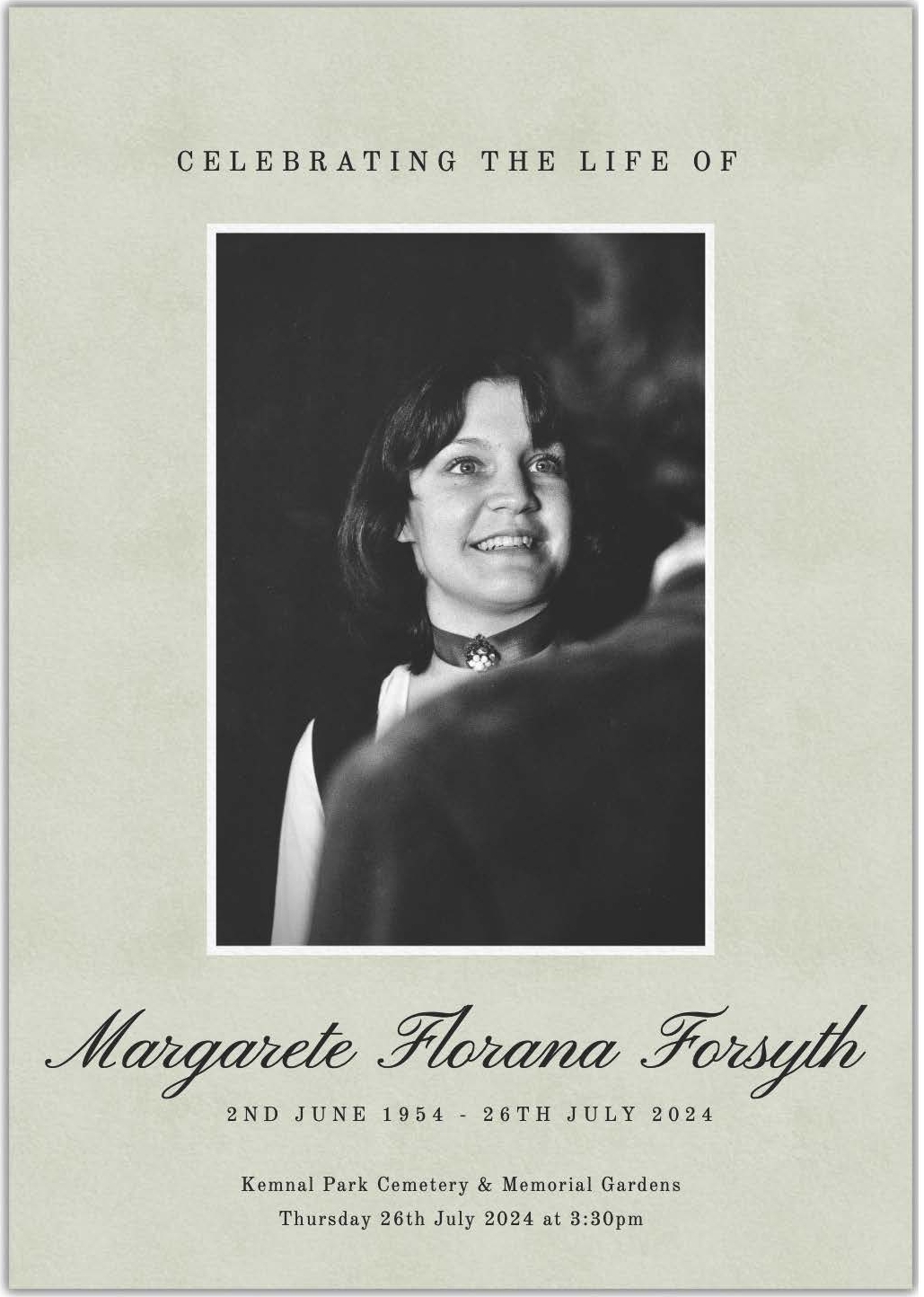

Margarete Forsyth, née Graffam,

2 June 1954–26 July 2024.

This is an expanded version of the eulogy delivered by Steven Elder on my behalf at Maggie’s funeral on 15 August 2024.

Goldsmiths’

Maggie and I met in September 1980, when we both arrived as new members of staff in the German Department of Goldsmiths’ College. Although we certainly took to each other from the start, I could never have imagined that I would one day be faced with helping to tell the story of her life, that she would turn out to have been the most remarkable person I was ever to meet, and that she would end her days meaning so much to so many people.

Like other colleagues, I was soon invited to dinner, meeting Julian and wee Dettmer for the first time in their rented flat in Westcombe Park. And there I started to learn more about the journey that had led her to London: from her birth in Nuremberg, her role as the eldest of seven siblings, her formative years in Ethiopia, the incredible breadth of her youthful reading, her outstanding academic record at university, and how she came to marry an English actor.

After a year of renting, the Forsyths bought the house in Charlton Road and that now became a very welcoming centre of hospitality, not to mention an ad hoc workshop for planning theatrical productions, making props, and sewing costumes. A year or two later, in order to shorten my journey to work, I moved from North London to Charlton, and so became a frequent visitor. The house always seemed full as the couple entertained (and fed!) friends, colleagues, and students, and Maggie started her theatrical career in earnest.

The first of these was Brecht’s Leben des Galilei (“Life of Galileo”), staged in the Drama Department’s 54-seat Studio 3. Drama were sufficiently impressed by this production that they gave her the College’s main stage, the 140-seat George Wood Theatre, with its superior technical facilities, for her subsequent productions: Wedekind’s Frühlings Erwachen (“Spring Awakening”) and Dürrenmatt’s Besuch der alten Dame (“The Visit”). Right from the start, even though the cast and crew were not professionals, these reached a high standard, and in the course of them she established firm relationships with a number of people who were to play a role at the start of her professional career, and indeed beyond.

The Fringe

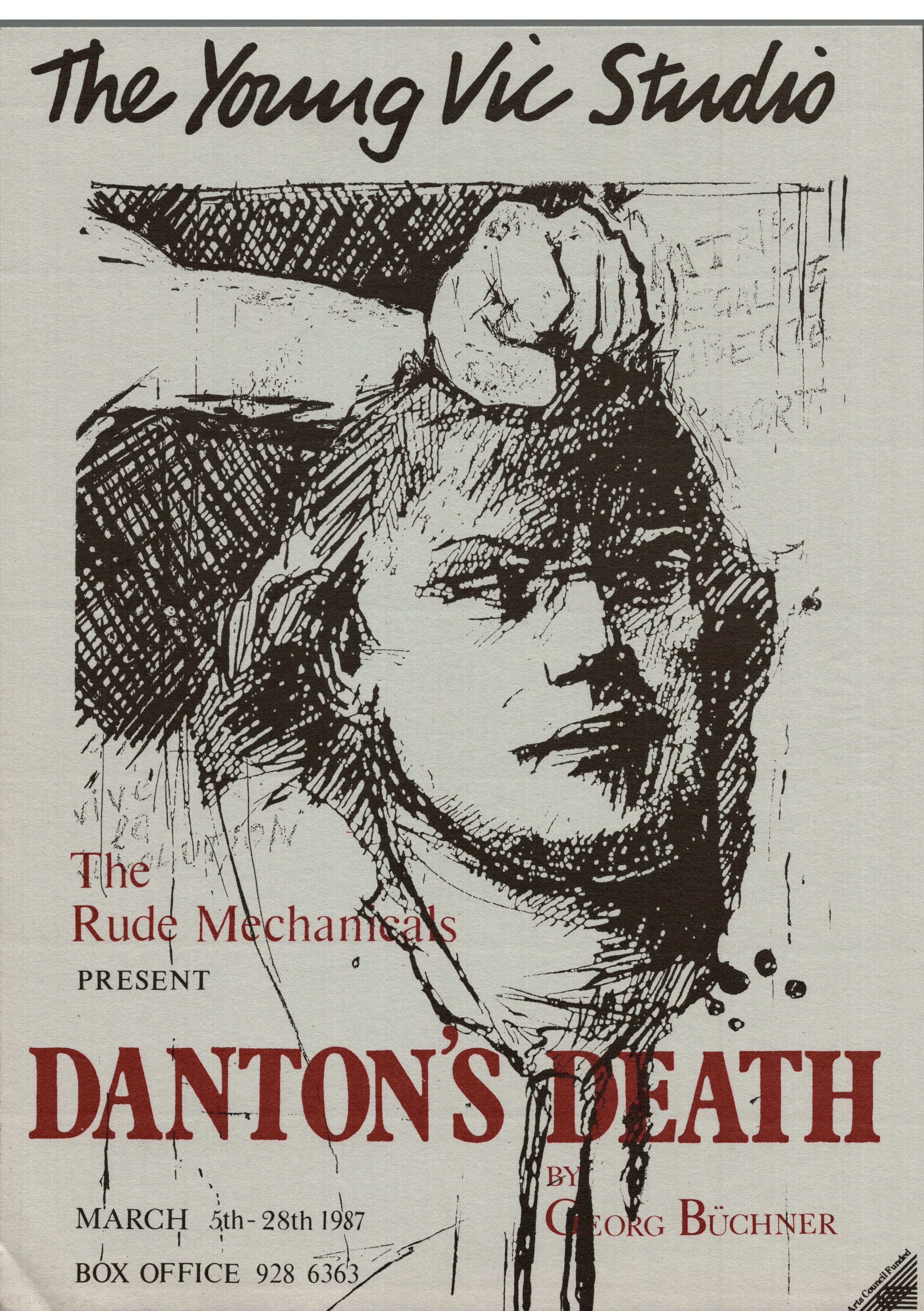

Maggie’s post at Goldsmiths’ was funded by the German Academic Exchange Service and it allowed for a maximum of four years. In September 1984, therefore, she necessarily left full-time employment and then took a series of temporary jobs while she began a PhD on modern productions of German classical drama. This was never to reach completion, but one of her thesis advisors was a co-founder of the Magna Carta Theatre Company. In March 1986 this gave Maggie the opportunity of mounting a production of Goethe’s Faust, Part I at the Young Vic Studio. Julian took on the role of Faust, while a number of Maggie’s former students covered backstage tasks. The Stage called it “exhilarating”.

The Rude Mechanicals

After a hiatus, the reasons for which I can no longer remember, The Rude Mechanicals’ final offering, in 1990, was The Life of Galileo. This was an important production for Maggie: for the lead role she managed to secure the services of Bernard Kay. With extensive stage, film, and television credits, he was by far the most experienced actor she had worked with. The two hit it off immediately: even though this was only her third professional production, Bernard readily embraced Maggie’s vision and approach, while she benefited from his unrivalled breadth of experience. Bernard was to act in many of Maggie’s later productions, never turning down any role she asked him to play.

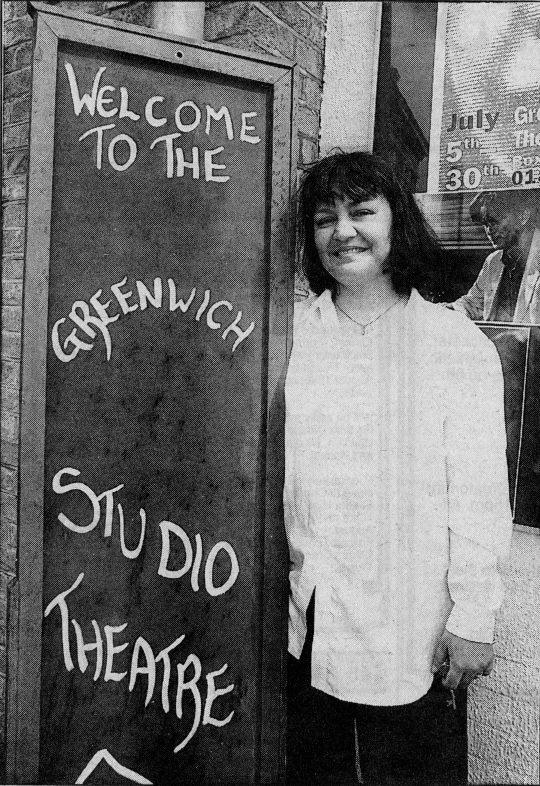

Greenwich Studio Theatre

They started with a short season of “Comedies of the Enlightenment” comprising Lessing’s Minna von Barnhelm and Holberg’s Erasmus Montanus. Over the next six years they mounted productions of ten more European plays — Austrian, French, German, Swiss — from the 1730s (Marivaux’s The Will) to the 1950s (Dürrenmatt’s A Spanner in the Works). Julian took charge of the scripts, while the staging was Maggie’s responsibility. She generally took on the set-design, too, often jointly with Vicky Emptage.

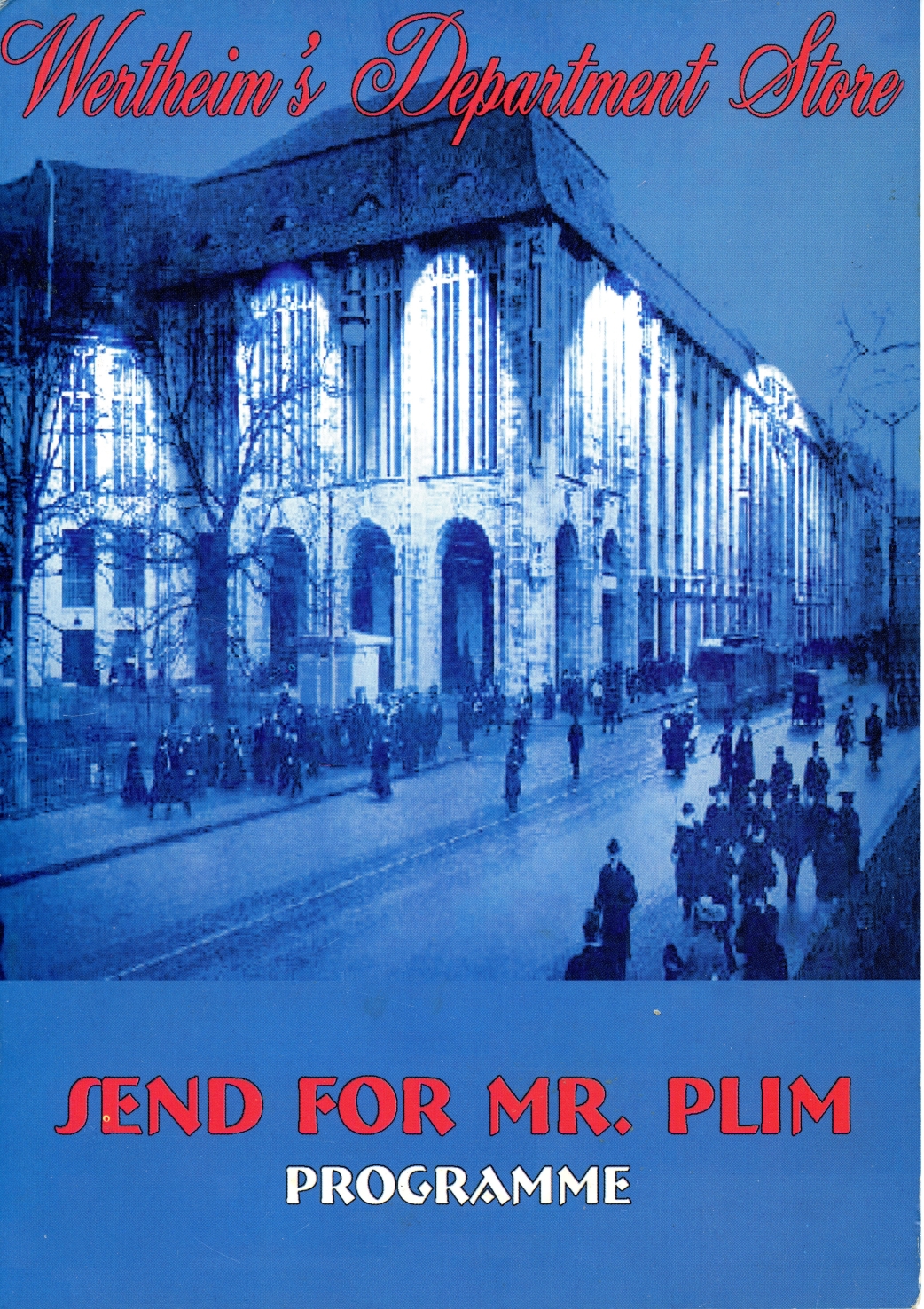

The company’s productions received an overwhelmingly positive reception from audiences and critics alike, and the theatre built up a regular local following, which led in turn to growing sponsorship, something necessary to keep such a small theatre — a mere 54 seats — in the black. The Times praised the company’s “resourceful staging in a small space”; The Guardian called Send for Mr Plim “a gem”, while The Independent offered an “unreserved recommendation” for A Spanner in the Works. For The Stage, The Green Parakeet was “beautifully paced and beautifully acted”.

After two years, however, relations with the Prince of Orange’s landlord had become difficult and the Forsyths had started looking for an alternative venue. Getting wind of this and no doubt fearing the loss of bar revenue, the landlord — to call him a shady character would be charitable — decided to run his own theatre with the same name. Shamefully, an actor Maggie had asked to help manage the GST agreed to assist with this venture. As if that weren't enough, the Forsyths’ access to the theatre was blocked and they were not even allowed to remove the GST’s equipment and props.

After the upheaval, the first productions were revivals, but four new works then followed, culminating in Mischa Spoliansky’s “cabaret opera” Send for Mr Plim, with the songs performed by Cantabile. This was a UK première. In a nice touch, since the piece is about a department store, Maggie invited Arding & Hobbs, located nearby, to send a few members of staff each evening to perform in non-speaking roles.

With such a clear demonstration of both her artistic vision and her ability to get the best out of actors, Maggie might reasonably have hoped that she would be able to move into the commercial theatre, perhaps even securing a permanent post as artistic director somewhere. Unfortunately, for whatever reason, this never happened, and by 2000 the burden of commuting to Battersea and the wish to explore other possibilities led her to suspend the GST’s activities for a time. Alas, they never resumed.

Beyond the Fringe

Even before the GST’s awards and nominations, the glowing reviews for The Rude Mechanicals’ work meant that Maggie was in demand for productions in London’s drama schools. 1990 saw the first of a number of these for Mountview, starting with Max Frisch’s The Fire Raisers. One of her students in that first group was Eddie Marsan, who went on to play roles in many of the GST’s productions. Other schools that called upon her included LAMDA, Webber Douglas, Rose Bruford, RADA, and The Drama Centre, and she became a regular at East 15, to whom she later donated the GST’s costume collection (the photo shows her with the East 15 cast of her 2006 production of Working). She and Julian also spent a very enjoyable term in 2004 at the University of Southern Florida’s annual “Brit School”, where she directed and designed a production of The Tempest, with Julian as Prospero.

And she had many other strings to her bow. With a strong visual imagination, she had always been heavily involved with the set design for her own productions and had frequently, in fact, undertaken it herself. In 2000, wishing to branch out within the theatre world she found she was able to fund a year’s course at Motley, the set-design school. This turned out, though, to be a slight disappointment: she certainly learnt some useful techniques, but she had underestimated how much stagecraft she had developed in her own productions. For, in addition to her artistic flair and considerable knowledge of historical design, she came to the course already well-versed in the art of creating a set to serve the demands of a play. Nonetheless, graduating from the course gave her a recognised qualification and thus the basis for working as freelance designer for other theatre companies, which had been her aim.

As if that wasn’t enough, she had other talents. She was certainly an accomplished interior designer and decorator, as you can tell from the commission she and Vicky Emptage received from Battersea Arts Centre to renovate their public toilets. For each toilet they used a different historical style of decoration — Ancient Egyptian, Classical, and the like, each with its own colour-scheme and distinctive mosaic motifs (see below). There was even a grand opening by the mayor, and, for once, gentlemen and ladies were permitted to visit each other’s loos to admire the new décor (alas, all this was lost in the BAC’s 2018 fire.)

Words

She could also write fluently, whether in German or in English, prose or verse, though she seems to have preferred verse. A witty poem of hers was recently included in a German anthology, and her children’s book in rhyming couplets, Hannibal, about the Ethiopian misadventures of a large pet tortoise, will soon, we must hope, find its public.

Many of the translation commissions were unexciting, to be sure, but even the dullest might involve interesting linguistic challenges. She had real pleasure in thinking up witty German advertising slogans to replace pun-filled and thus untranslatable English ones — the clients were typically astonished at her virtuosity. There were some real dream jobs, too, where the topic matched her personal interests and expertise: booklet notes for classical CDs, or catalogues for art exhibitions. For one client she had to invent dozens of evocative names for paint colours, something that’s well beyond simple translation.

Illness and Resilience

But an appalling tale of medical negligence put paid to that vision of the future. She had had concerns about her throat for some years, but was still taken aback with the cancer diagnosis she received at the end of 2007. It was one that could and should have been made years earlier, at a stage when drug treatment would have sufficed. This oversight meant that surgery was the only option. Always diligent in research, Maggie discovered a surgeon in Düsseldorf who could offer a less drastic outcome than the NHS, which she now didn’t trust anyway. Even so, it was a long process — forty operations over five years — and she was inevitably left with life-changing consequences: her true speaking voice was gone for good, nor was she ever again able to sing, and it made the theatre career she had envisaged all but impossible.

She still, in fact, managed one or two smaller-scale theatrical projects. Most were local, like the staging of Bach’s Coffee Cantata using the whole of the main hall in Charlton House, or the very enjoyable time she had at the local community centre once a week getting a group of three-to-five-year-olds to act out passages from Peter and the Wolf. But in 2017 she also staged a one-off “workshop performance” of Plim, which Julian had revised since the GST days, for an invited audience in a West End theatre.

More recently, however, life again became harder, as longer-term consequences of surgery brought further unwelcome changes. She was often able to sleep only a few hours a night, and in her worst moments every breath seemed to require a conscious effort. But she was curiously unwilling to let people see the true extent of her difficulties. She would still unstintingly do things for other people, even if it now cost her much more effort than before. She continued to spend hours every week providing companionship for her friend Lois, increasingly lost to Alzheimer’s. All in all, I think it’s fair to say that she was sometimes too good a human being for her own good.

She never gave up: she carried on doing her best to be creative (keen to finish Hannibal), to be there for friends when they needed help, advice or comfort, and to produce, as before, world-class dinners for the gourmets and gluttons among her circle.

A Conclusion?

But the fact that Maggie’s last years were so full of challenges and, yes, a good deal of physical distress, should not lead us to forget the immense enjoyment she derived from life and from art in its many forms, all she so unselfishly gave us and many others, all that she created or inspired others to create.

And, of course, that is not entirely the end of the story. Maggie’s artistic legacy lives on in the work of those she taught and those whom she nurtured in her own productions. But there is also unfinished business for the Forsyth estate: most of the new translations done for The Rude Mechanicals and the GST have yet to be published, and, needing only a suitable illustrator, Hannibal is almost ready for its readers. It would be good, too, if the revised version of Send for Mr Plim could be given a proper theatre run before too long. But those are matters for another time.

A Final Thought

Now I realise that, at this point, we’re all feeling pretty wretched, at what we have lost, at Maggie’s sad end. But there is a whole group of people I would prefer you to feel sorry for, and I mean really sorry. We are the lucky ones! — we knew this extraordinary woman, we had the benefit of her creativity, her hospitality, her advice and comfort, her good company, her loyalty, her love and friendship. We all have plenty of memories. And our grief, I dare say, will lessen in time. But spare a thought for those poor souls who never knew her, those who now never will — they can feel only everlasting regret for what they have missed.

Peter Christian, 7 October 2024

- Maggie in London: Reminiscence and Eulogy

- Remembering the Life of Margarete Florana Forsyth, 15th August 2024 (Video of funeral service)

- Obituary in The Stage, 25 September 2024 (PDF)

- Maggie Forsyth Obituary (The Guardian: “Other Lives”, 3 November 2024)

- Working with Maggie (Alex Wardle, Lighting Designer)