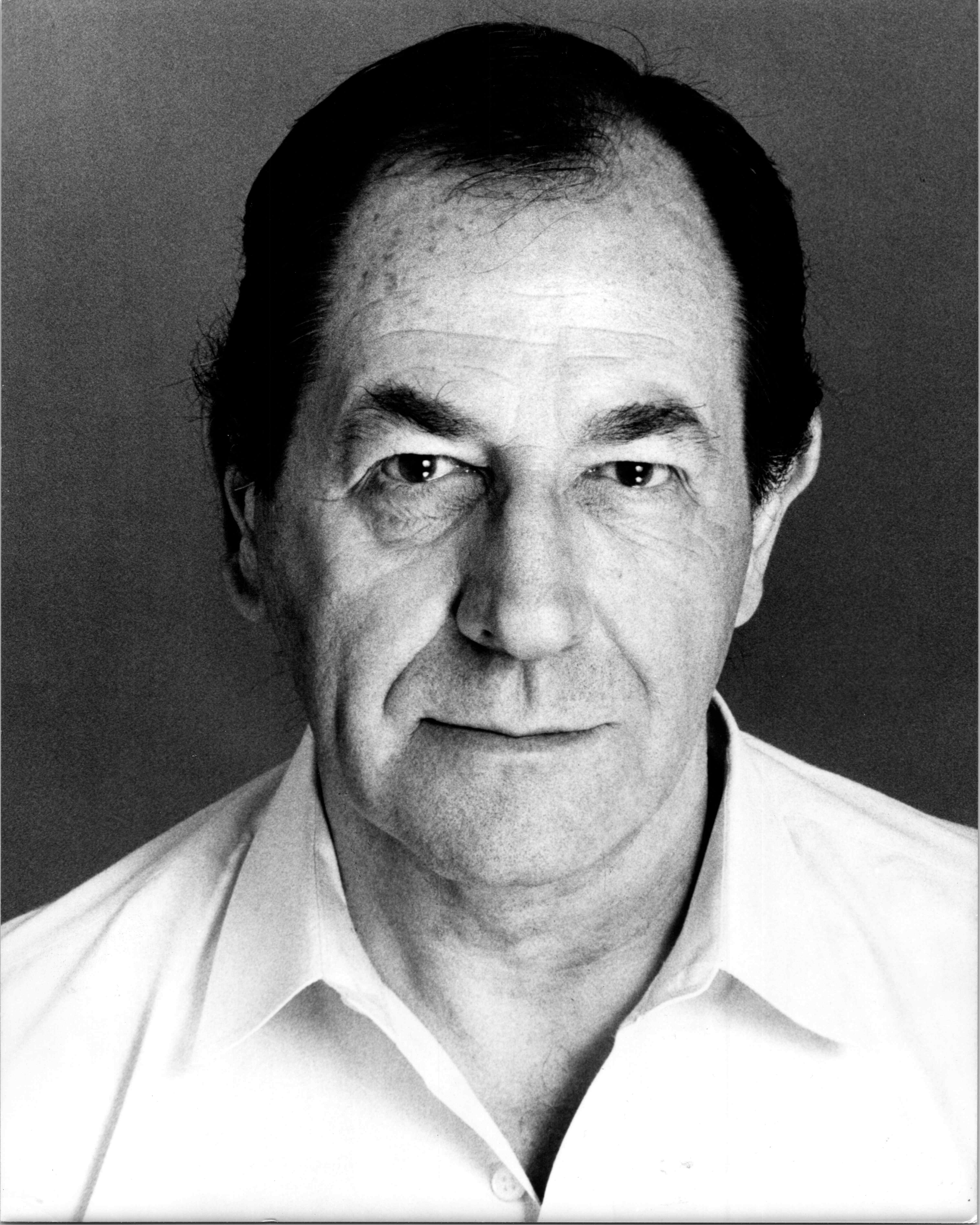

Remembering Bernard Kay

Margarete Forsyth

Delivered at Bernard’s funeral, 21 January 2015

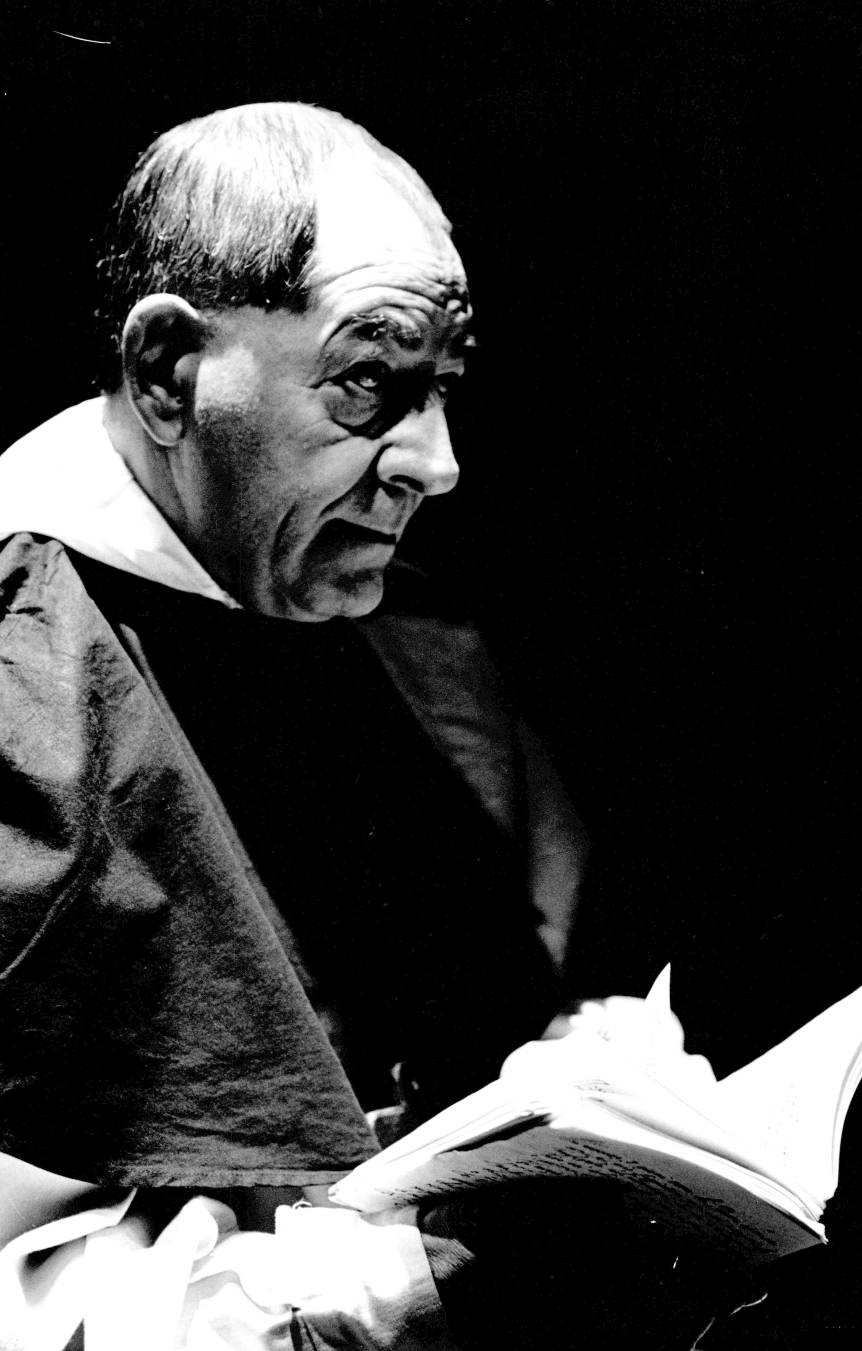

Four hours and as many glasses of wine later Julian came to find us. Bernard and I hadnít stopped talking and I felt I had known him for years. Of course he had at some time during that evening agreed to play Galileo and of course I was a little nervous again before the first rehearsal, as his theatre CV was as long as mine was short. I had also heard through the theatre grapevine that he could be a “difficult actor” opinionated, headstrong and argumentative. I neednít have worried. He made me feel completely at ease and I enjoyed every minute of rehearsal with him. Of course we debated, argued, disagreed, fought over the interpretation of lines, but it was always in the cause of serving the text, finding the right interpretation, making things “real” and clear to the audience. And at the end of each rehearsal, we would go out for a drink together and start debating about the play and his part all over again. I learnt more about acting from him in those rehearsal weeks than from almost anybody else, and he gave me the confidence to go on working as a director for the next 20 years.

Bernard took acting very seriously, it was his life, but he never took himself too seriously and was always extremely modest about his achievements. When we put together the biographies for the Galileo programme at the Young Vic, he insisted on putting in the following about him:

“Bernard Kay trained up the road at the Old Vic Theatre School. Bravest/stupidest claim to notoriety: learned, rehearsed and played Macbeth in twenty hours at the Old Nottingham Playhouse. (Well the world was young.) Jobbed around from Crossroads to Olivierís Titus Andronicus via Dr Who and Dr Zhivago. Still waiting to be bored by the business.”

When I was diagnosed with throat cancer I could not work as a director for a long time, but we kept on meeting up on a regular basis when I was not in hospital, mainly in the Charing Cross Hotel restaurant, as Bernard loved going out and the place was quiet. This was essential for our communication. We were a right pair: Bernard was deaf in his left ear and I could only whisper. But that did not stop our debates about life, love, politics, death and of course as always theatre. I filled notebook after notebook with questions and comments and he would answer in his wonderful deep voice and tell me stories of his life for many hours and as many glasses of wine.

We dreamed of doing King Lear together, but that was not to be.

As for all of us, it was a shock to me when he decided to take his last bow, not because I did not understand it — I totally did — but because I now feel this big gap in my life.

When I had my first operation in a German hospital Bernard sent me a huge bunch of flowers with a note saying “All is forgiven. Please come back!” I donít think the German nurses understood why I laughed so much.

In Brechtís Galileo the Pope says something about Galileo that in my view sums up the special man Bernard was too:

He enjoys himself in more ways than any man I have ever met. His thinking springs from sensuality. Give him an old wine or a new idea, and he cannot say no.”

After The Life of Galileo, Bernard went on to act in the following Greenwich Studio Theatre productions by Margarete Forsyth:

- Lessing, Minna von Barnhelm (1993)

- Holberg, Erasmus Montanus (1993, 1994, 1996)

- Diderot, The Nun (1994, 1996)

- Schnitzler, The Green Parakeet (1994, 1995)

- Maggie in London: Reminiscence and Eulogy

- Remembering the Life of Margarete Florana Forsyth, 15th August 2024 (Video of funeral service)

- Obituary in The Stage, 25 September 2024 (PDF)

- Maggie Forsyth Obituary (The Guardian: “Other Lives”, 3 November 2024)

- Working with Maggie (Alex Wardle, Lighting Designer)